Wednesday, October 29, 2025

Frances Perkins

Monday, October 27, 2025

Indoor flying!

And here's another one of a group. I couldn't embed it, so you'll have to paste this into your address bar: https://www.facebook.com/watch?v=1077659960343905Please replace breakdancing on the Olympics with this pic.twitter.com/kTCsEc7dmP

— Interesting As Fuck (@interesting_aIl) October 26, 2025

Wednesday, October 22, 2025

Saturday, October 18, 2025

Isaac Asimov: A Cult of Ignorance - And More

On January 21, 1980, Newsweek magazine published an article by Isaac Asimov entitled "A Cult of Ignorance," which has resonance in the context of today's world. Here it is, with a foreword by Alexander Atkins, of Atkins Bookshelf:

If you have watched any of the recent impeachment hearings or the President’s recent State of the Union Address, not to mention general coverage of politics over the past few years, one must sadly arrive at the inescapable conclusion that we are living in a post-truth world, where Truth does not matter, where a belief or opinion — no matter how ill-informed or irrational — has trumped (pun intended) objective facts. In short, we are living in an Orwellian world. Indeed, George Orwell’s dystopian novel (written more than seven decades ago) is a magnifying glass that exposes how language and disinformation is used as a powerful political tool to conceal the truth in order to manipulate the masses. Listen to these notable lines from 1984: “The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command… In the end the Party would announce that two and two made five, and you would have to believe it… Orthodoxy means not thinking — not needing to think. Orthodoxy is unconsciousness… And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed — if all records told the same tale — then the lie passed into history and became truth.” It’s eerie isn’t it?

But few know that another influential writer and intellectual would mine this same territory thirty years later — as the actual year 1984 approached. For many years, Newsweek magazine contained a feature titled “My Turn” where a notable individual wrote about any issue that they felt was important. For the January 21, 1980 issue, world-renown science fiction writer Isaac Asimov wrote a very thought-provoking essay titled “A Cult of Ignorance” that is as relevant today as it was 40 years ago. Interestingly, the essay was never reprinted in any collection of essays — a disservice to what Asimov saw then and is happening now: the rise of anti-intellectualism. So what does anti-intellectualism mean? Anti-intellectualism, according to Richard Hofstadter, professor of American history at Columbia University, public intellectual, and author of Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963), is defined as “resentment and suspicion of the life of the mind and of those who are considered to represent it; and a disposition constantly to minimize the value of that life.” In his essay, Asimov argues that there is a cult of anti-intellectualism in America that perpetuates a very flawed concept of democracy: that every person’s opinion, whether ill-informed or well-informed, is considered equal. Stated another way, in a democracy, equality of rights does not necessarily mean equality of knowledge — an opinion formed on the basis of lies does not have the same significance of an opinion based on objective facts. And this is something that politics parties misuse to their advantage: it is in their best interest to disseminate lies, to perpetuate ignorance — indeed, to create a cult of ignorance — to manipulate the masses. And here are some of critical questions: can we ever get back to a world that values Truth? How do we do it? How long will it take?

Here is Asimov’s essay, “A Cult of Ignorance,” for your consideration and discussion:

It’s hard to quarrel with that ancient justification of the free press: “America’s right to know.” It seems almost cruel to ask, ingenuously, “America’s right to know what, please? Science? Mathematics? Economics? Foreign languages?”

None of those things, of course. In fact, one might well suppose that the popular feeling is that Americans are a lot better off without any of that tripe.

There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that “my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.”

Politicians have routinely striven to speak the language of Shakespeare and Milton as ungrammatically as possible in order to avoid offending their audiences by appearing to have gone to school. Thus, Adlai Stevenson, who incautiously allowed intelligence and learning and wit to peep out of his speeches, found the American people flocking to a Presidential candidate who invented a version of the English language that was all his own and that has been the despair of satirists ever since.

George Wallace, in his speeches, had, as one of his prime targets, the “pointy-headed-professor,” and with what a roar of approval that phrase was always greeted by his pointy-head-audience.

Now we have a new slogan on the part of the obscurantists: “Don’t trust the experts!” Ten years ago, it was “Don’t trust anyone over 30.” But the shouters of that slogan found that the inevitable alchemy of the calendar converted them to the untrustworthiness of the over-30, and, apparently, they determined never to make that mistake again. “Don’t trust the experts!” is absolutely safe. Nothing, neither the passing of time nor exposure to information will convert these shouters to experts in any subject that might conceivably be useful.

We have a new buzzword, too, for anyone who admires competence, knowledge, learning and skill, and who wishes to spread it around. People like that are called “elitists.” That’s the funniest buzzword ever invented because people who are not members of the intellectual elite don’t know what an “elitist” is, or how to pronounce the word. As soon as someone shouts “Elitist” it becomes clear that he or she is a closet elitist who is feeling guilty about having gone to school.

All right, then, forget my ingenuous question. America’s right to know does not include knowledge of elitist subjects. America’s right to know involves something we might express vaguely as “what’s going on” in the courts, in Congress, in the White House, in industrial councils, in the regulatory agencies, in labor unions — in the seats of the mighty, generally.

Very good. I’m for that, too. But how are you going to let people know all that?

Grant us a free press, and a corps of independent and fearless investigative reporters, comes the cry, and we can be sure that the people will know.

Yes, provided they can read!

To be sure, the average American can sign his name more or less legibly, and can make out the sports headlines — but how many non-elitist Americans can, without undue difficulty, read as many as a thousand consecutive words of small print, some of which may be trisyllabic?

Moreover, the situation is growing worse. Reading scores in the schools decline steadily. The highway signs, which used to represent elementary misreading lessons (“Go Slo,” “Xroad”) are steadily being replaced by little pictures to make them internationally legible and incidentally to help those who know how to drive a car but, not being pointy-headed professors, can’t read.

Again, in television commercials, there are frequent printed messages. Well, keep your eyes on them and you’ll find out that no advertiser ever believes that anyone but an occasional elitist can read that print. To ensure that more than this mandarin minority gets the message, every word of it is spoken out loud by the announcer.

If that is so, then how have Americans got the right to know? Grant that there are certain publications that make an honest effort to tell the public what they should know, but ask yourselves how many actually read them.

There are 200 million Americans who have inhabited schoolrooms at some time in their lives and who will admit that they know how to read (provided you promise not to use their names and shame them before their neighbors), but most decent periodicals believe they are doing amazingly well if they have circulations of half a million. It may be that only 1 per cent — or less — of Americans make a stab at exercising their right to know. And if they try to do anything on that basis they are quite likely to be accused of being elitists.

I contend that the slogan “America’s right to know” is a meaningless one when we have an ignorant population, and that the function of a free press is virtually zero when hardly anyone can read.

What shall we do about it?

We might begin by asking ourselves whether ignorance is so wonderful after all, and whether it makes sense to denounce “elitism.”

I believe that every human being with a physically normal brain can learn a great deal and can be surprisingly intellectual. I believe that what we badly need is social approval of learning and social rewards for learning.

We can all be members of the intellectual elite and then, and only then, will a phrase like “America’s right to know” and, indeed, any true concept of democracy, have any meaning.

*****

Click here for an article at The Guardian by Sophie McBain entitled "Are we living in a golden age of stupidity? McBain talks about the pernicious influence of AI, and particulrly generative AI, on the education of today's students, and argues that they are becoming more and more dependent on AI to do their homework for them, such as essay assignments.

One frighening statistic: While tests measuring 15-year-old students' ability in reading, math, and sciences showed steady improvement throughout the 20th century and into the 21st -- largely due to better and more widespread education, but also because of other factors, such as decreased poverty and better nutrition -- that progress peaked in 2012, and has been gradually falling since then.

Sunday, October 5, 2025

The incredible Mark Knopfler: Sultans of Swing

''When I watch this I'm back in my living room, as a 14 year old, with my Mum, Dad and elder brother. They are all gone now, I am not, and the music will always bring them back to me.''

— Rock'n Roll of All (@rocknrollofall) October 5, 2025

''I love how Mark just improvises the lyrics so he can play the guitar just how he wants it… pic.twitter.com/HOtfDFyooX

Farewell message from Dr. Jane Godall

Beautiful. A rebel and a warrior to the end.

— John Rocha (@TheRochaSays) October 5, 2025

So many rebels get soft and become the establishment as they get older. Thank God that we still have those rebels (like George Carlin and others) who’ll fight to the end. https://t.co/4ibJwq1oDf

Beginning gaming?

I asked ChatGPT to recommend a first-person shooter for a PC, and got the following response:

🎯 1. Portal 2 (Valve)

-

Type: Puzzle-based first-person game (no combat).

-

Why it’s great for beginners: Teaches movement, camera control, and first-person navigation without any pressure. It’s witty, clever, and relaxing.

-

Bonus: You’ll finish it feeling confident handling any FPS camera.

🚀 2. Halo: The Master Chief Collection (especially Halo: Combat Evolved or Halo 3)

-

Type: Classic sci-fi shooter with a campaign.

-

Why it’s great: Intuitive controls, clear visuals, forgiving enemies on easy mode, and strong aim assist if you use a controller.

-

You’ll learn: Movement, aiming, weapon management, and basic shooter flow.

🏜️ 3. Borderlands 2 or 3

-

Type: Story-driven “looter shooter” with RPG elements.

-

Why it’s great: Tons of fun, colorful style, and leveling up makes it forgiving if you miss shots.

-

You’ll learn: Gunplay variety, exploring, and managing upgrades.

👻 4. Far Cry 5 or Far Cry 6

-

Type: Open-world adventure shooter.

-

Why it’s great: You can approach missions however you want — stealthy or loud — and difficulty can be adjusted at any time.

-

You’ll learn: Exploration, stealth, long-range aim, and using vehicles.

🧟 5. Bioshock: The Collection

-

Type: Narrative-driven sci-fi/horror shooter.

-

Why it’s great: Great story and pacing; easy modes let you enjoy the plot without dying constantly.

-

You’ll learn: Aiming, use of powers (“plasmids”), and FPS storytelling.

🔫 6. Call of Duty: Modern Warfare (2019)

-

Type: Military shooter campaign (you don’t have to play online).

-

Why it’s great: Polished controls, stunning visuals, and short, self-contained missions.

-

You’ll learn: Realistic weapon handling, cover use, and situational awareness.

🕹️ If you want to start super gently

Try Portal 2 first — it’s relaxing and will make normal shooters feel natural afterward.

Then move to Halo or Far Cry 5 — both are intuitive and rewarding for first-timers.

Friday, October 3, 2025

Bad Bunny to perform at the Super Bowl

Wow ... thank-you for the history lesson. I now understand ... https://t.co/DJ0fP9fGEu

— The Ravina Project (@ravinaproject) October 3, 2025

Wednesday, October 1, 2025

Here's an entry on Substack by Paul Krugman, about Pete Hegseth's moronic meeting with the nation's top generals and admirals at Quantico, Virginia, entitled "Bulging Biceps Don't Win Modern Wars":

Why did Pete Hegseth, the defense secretary — he may call himself secretary of war, but Congress has not, in fact, voted to change his department’s name — summon 800 top generals and admirals to Washington? I admit that I feared the worst — that he would demand that they pledge personal fealty to Donald Trump. But no: They were summoned to listen to a speech about “lethality,” followed by a highly political speech by Trump himself.

How do you achieve lethality, according to Hegseth? By telling the military that it’s OK to engage in hazing, sexual abuse and bigotry — he didn’t say that explicitly, but that was his clear message. Also, war crimes are no big deal. And members of the military, including the top brass, must shave their beards, lose weight and do pullups.

Hegseth’s speech was morally vile. It was also, however, profoundly stupid. Hegseth seems to have gotten his ideas about what an effective military looks like by watching the movie 300.

I am, of course, by no means a military expert myself. But I read and talk to people who are military experts, and think I have some idea about how modern wars are fought. Furthermore, there’s a clear family resemblance between Hegsethian stupidity about modern war and Trumpian stupidity about economic policy. Modern nations don’t achieve prosperity by emphasizing “manly” jobs; they don’t win wars by having big biceps.

War still requires extraordinary courage from the men and women engaged in combat — courage that, according to officers I’ve spoken with, is rooted in a sense of honor, not swaggering machismo. Combatants also have to be physically fit enough to endure incredible hardship.

But they don’t have to look like bodybuilders — and anyway, only a small fraction of a modern army engages directly in combat. These days, war is conducted largely with machines and ranged weapons, and most of an army’s personnel are employed, one way or another, keeping those machines and weapons in action and providing the intelligence that makes them effective. These noncombatants are every bit as essential to victory as front-line troops.

Actually, this has been true for a long time, at least since World War II. I very much doubt that Hegseth would consider the team led by Alan Turing, which broke Germany’s Enigma code, or the group led by Joseph Rochefort, which broke Japan’s naval code, warriors — even leaving aside the fact that Turing was gay. Yet they contributed as much to victory as any front-line soldier.

And the “warrior ethos” Hegseth touts is even less sufficient, on its own, to win wars today.

We don’t have to speculate about what a 21st century war would look like, because there’s ferocious, dare I say lethal, combat happening in Ukraine as you read this.

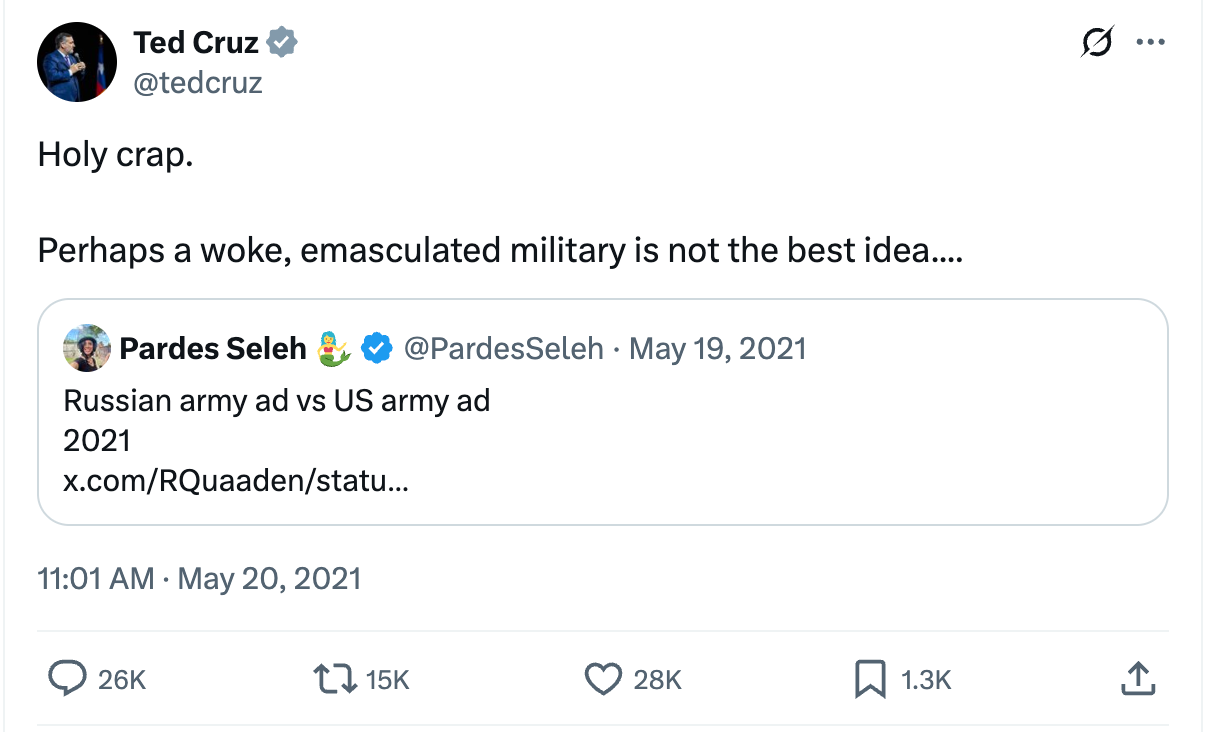

Some readers may recall how impressive many politicians on the right found Russia’s army before it tried to conquer Ukraine:

But it turned out that the Russian army was much better at looking tough than it was at actually waging war. All that non-woke masculinity didn’t prevent Russia’s initial attempt to seize Kyiv from becoming an epic disaster.

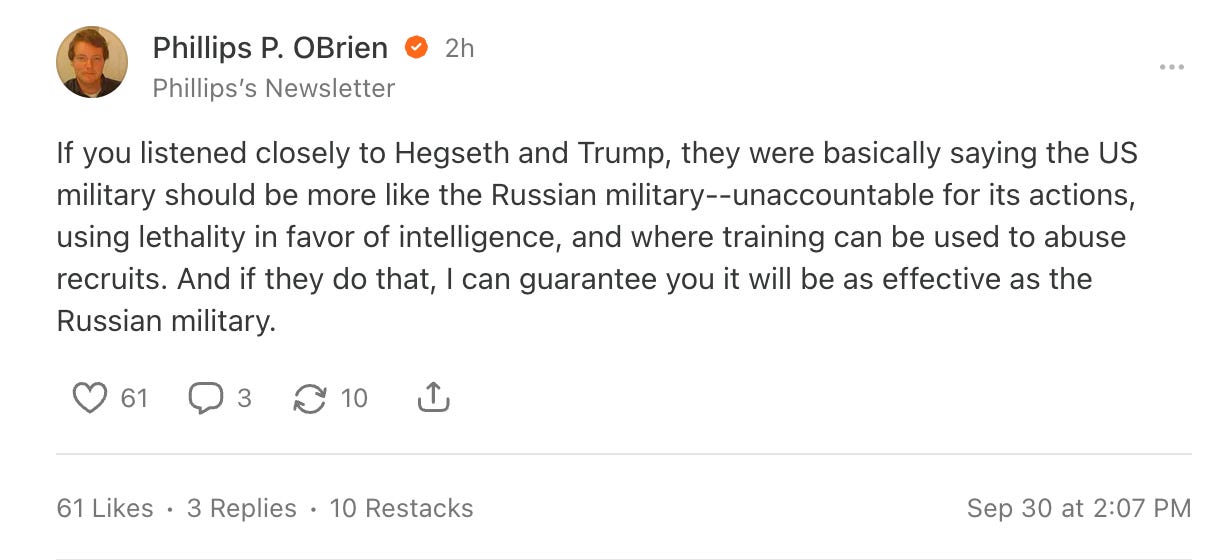

And while the war goes on, and on, and on, it’s now waged largely with drones and cruise missiles, not well-groomed guys with six-pack abs. As the military historian and analyst Phillips O’Brien wrote in a recent Substack post, technology has turned large parts of the Ukraine battlefield into “kill zones” — sort of like No Man’s Land in World War I, but 40 or more kilometers wide. Sending men into these zones, no matter how tough they look, is just a way to throw their lives away.

The Ukrainians, although outnumbered, have held their own in this new kind of war, not by being tougher than the Russians — although they are awesomely, almost inconceivably tough — but by being smarter, more flexible and more innovative, virtues I doubt loom large in Hegseth’s concept of lethality.

But Hegseth and Trump, not surprisingly, have learned nothing from this story. Here’s how O’Brien summarized it in a note yesterday:

I’d add that a military rife with sexual abuse and bigotry isn’t going to attract the best minds — many of which, although people like Hegseth will never believe it, reside in female and nonwhite bodies.

As I said, all of this is of a piece with Trumpian policy in other domains. Of course a regime that believes it can make America great by defunding science and destroying higher education believes that it can make our military more effective by making it prejudiced and stupid.

The good news is that America’s officer corps isn’t stupid, at least not yet. The stony silence with which the assembled generals and admirals greeted Hegseth’s and Trump’s rants was eloquent.

But you can now add the military to the list of great American institutions that MAGA is, in effect, trying to destroy.